The Tasmanian Tiger Thylacinus cynocephalus

Commonly known as the Tasmanian Tiger, the Thylacine is one of Australia’s best-known native marsupials. The species was first described in 1808 by Tasmanian naturalist G.P. Harris, as Didelphis cynocephala (‘dog-headed opossum’). Its genus was corrected in 1824 by Temminck to mean ‘dog-headed pouched-dog’. Over the following years the Thylacine evoked alot of attention, and thus in 1917 with the approval of King George V, a pair of Thylacines were represented on the Tasmanian Coat of Arms.

Description

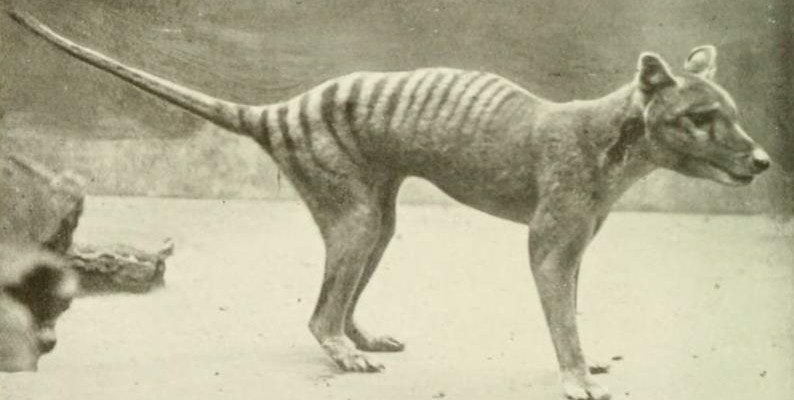

The largest of the carnivorous marsupials the Thylacine had a large head, small pointed ears, large black eyes and short legs. Adults measured approx. 1.8m from nose to tail and stood nearly 60cm high at the shoulder, with an average weight of 25kilos. It had sandy-brown coloured fur with 15-20 dark brown bands increasing in width towards its hindquarters. The rump tapered into a semi-rigid tail thickening where it met the body, a blackish tip and a slight crest above and below. Its powerful jaw and head muscles operated a mouth with an extraordinarily large gape of 120o.

The only sound made by a Thylacine was a husky, coughing bark, rapidly repeated when anxious or disturbed. They swam well and readily crossed rivers in pursuit of their prey. A Thylacine skull can be distinguished from that of a large dog by the number of incisor teeth, and the inflection of the angle of the lower jaw. Recognisable from a dogs footprint, the Thylacine had five short toes at the front set a centimetre from the palm, the fifth showing only as a claw mark. The hind foot had four short toes and blunt claws.

Distribution

Fossils and bone fragments of Thylacines have been found in caves and superficial deposits in most states of Australia and the eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea, where they lived until fairly recent in geological time. An intact Thylacine mummy was found in a cave on the Nullarbor Plain, WA and has been radio-carbon dated between 4,600-4,700 years old. Specimens found have ranged from the Pleistocene era to 3,000 years old.

Habitat

Once widespread in Tasmania, the Thylacines range extended from the mountain-tops 1200m above sea level to the coast, but was not so common in the rainforest or the button-grass plains of the south-west. They hunted on the open plains between forests, occurring in large numbers in the Lake District. Their preference being for open forest, woodland and grassy plains.

Shelter requirements

The Thylacine sought refuge during the day in sheltered rocky outcrops, occasionally emerging during cold weather to bask in the sun. On wet days they were neither seen nor heard. They reared their young in a lair found in hollow trees or rock cavities. Juveniles were observed in a nest, like that of a tent-like shelter in a dry fern-bed under the dropping and still attached dead fronds of a tree-fern

Reproduction

The Thylacines breeding season extended through winter and spring, when the females give birth to a litter of two or three. Like most marsupials, these are born at an early development stage, tiny and hairless. After making their way by crawling into their mother’s rear-opening pouch, the minute joeys each attached themselves to one of four teats. Here they would be carried for the first three months of life. With the fast-developing young inside, the pouch expanded to the extent it almost touched the ground. When old enough to leave the pouch, the young would be left in the nest while the female hunted. After weaning they would accompany their mother, until able to hunt independently. Males were larger than females, and in both sexes the head became slightly wider with age.

Diet

A predatory animal, the Thylacine hunted mainly at night usually solitarily, sometimes in twos. It located its prey by scent, then pursued it relentlessly, sometimes for several hours, until the prey was exhausted and could be killed. This was done in a characteristic way by crushing the skull with its powerful jaw. The Thylacines gait appeared stiff and awkward, and was not fast. The downward slope of the hindquarters and the stiffly held tail which rigidly united to the spine, forced the animal to run with a peculiar loping movement. The animal was not particularly agile, but lack of speed was compensated for by its stamina. The Thylacines main diet consisted of kangaroos, wallabies, but also included small mammals, ground-game and reptiles. They appeared to have a liking for vascular tissue, often only blood, liver and kidney fat were eaten but would also consume tails of prey for roughage. They were also known to have layed in wait for their prey, taking it by surprise.

Bounty schemes

In 1835 the Van Diemen’s Land Company offered the first bounty. By 1863, Thylacines were confined to remote and mountainous areas. Between 1878 and 1893 a Tasmanian tannery exported 3,482 skins to London to be made into waistcoats. From April 1888 the Tasmanian Government bounty scheme was enacted: one pound paid for an adult animal; 10 shillings a sub-adult. Between 1888-1914, records show that 2,268 bounties were paid for the Thylacine. Fur-trappers also poisoned the thylacine to reduce their raiding on snare-lines. By the 1900’s the species was becoming rare. An epidemic of a distemper-like viral disease is thought to have caused a population crash in 1905-1915, also affecting the Tasmanian Devil and Spotted-tailed Quoll 1908-1910 and on the mainland the Eastern Quoll. In 1909 a newspaper advertisement offered ‘tiger shoots for visitors in search of fun’. In 1910 the Government Bounty scheme ended, but the company bounty lasted till 1914.

Captive specimens

Thylacine’s were kept in a number of Zoos in Tasmania, the mainland and overseas. In January 1863, a female with three pouch young was sent to London Zoo. From Launceston, an adult pair was shipped, arriving in London in Nov 1884. The male died in Feb 1891, and the female April 1893 – the longest known specimen in captivity. Between 1910-1921, live Thylacines were shipped to three mainland zoos: Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. In 1926 The London Zoo bought its last Thylacine for 150 pounds. The Thylacine featured occasionally in Melbourne’s collection until 1929. Some two dozen animals were exported to overseas zoos including London, New York, Berlin and Washington. Over 150 specimens were once housed within Australian zoos. The last Thylacine shot in the wild was a young animal on a farm at Mawbanna in the State’s north-west, in May 1930. The last known specimen was snared in 1933 in the Florentine Valley and sold to Hobart Domain Zoo, where it died in September 1936.

The Warnings

As early as 1863 John Gould warned of the Thylacine: ‘When the comparatively small island of Tasmania becomes more densely populated, and its primitive forests are intersected with roads from the eastern to the western coasts, the number of this singular animal will speedily diminish, extermination will have its full sway, and be recorded as an animal of the past.’

An Article in the Zoological Society Bulletin of New York, July 1918 by W.H.D. Le Souef, then director of the Zoological Gardens of Melbourne states ‘The only way that native animals surely can be preserved for those that come after us is to form reserves in various types of country. Tasmania is sure to lose the Thylacine before long, as the dense brush is cleared and the country becomes more thickly settled. Even now it is scarce, and the settlers snare and destroy it whenever they get the opportunity.’

In 1923, Charles Barrett wrote of the Thylacine ‘He is rare now, and the days of his race are numbered.’ And then in 1943, ‘The Thylacine has become so rare that it seems doomed to extinction, strict protection having come too late’.

Ironically, the year that the last zoo individual died (1936), the Thylacine was given official protection by Tasmanian Law.

In search of…

The species was well established in Tasmania when Europeans first arrived in 1788, then known as Van Dieman’s Land. Now presumed extinct, although there have been many alleged sighting of the Thylacine, there is no hard evidence of its continued existence. Between 1937 and 1985, searchers spent over half a million dollars looking for some conclusive evidence of the animal. Expeditions are still being funded in an attempt to rediscover it living in the remote northeast or northwest of the state. In 1980 an intense and comprehensive search was made, but failed to provide proof of its survival. The last conclusive sighting to date of the Thylacine was in March 1982 by an officer of the Tasmanian National Parks and Wildlife Service, in the Tarkine wilderness on the north-west coast.

In Conclusion

The tragedy of the Thylacine is that its demise was so unnecessary. Early naturalists warned of the fragile state of the Thylacine population. The Tasmanian Advisory Committee (for native fauna) recommended that the animal be placed on the totally protected list in 1928. This suggestion met with widespread opposition from landowners and was thus defeated.

Of the six marsupial carnivores in Australia, the Thylacine is now officially extinct, the Western Quoll is endangered and maintained in the wild only by constant targeted fox-baiting programs, the Spotted-tailed Quoll and Eastern Quolls are listed as potentially vulnerable, and a decline has been noticed in the Northern Quoll. Only the Tasmanian Devil seems secure at present.

Hunting of the Thylacine, combined with loss of habitat, contributed to the decline of the species. Man must grasp the irrefutable fact that modern civilisation radically changes the environment and extraordinary measures are necessary to preserve these ecologically significant species. So they too do not suffer the fate of the Thylacine, protected only in the twilight of its existence.

© Donna Racheal 2007